A conversion model deals with the transformation of targets into advocates. Conversion models match the consumer decision-making process whereby the marketer makes an individual aware of the product, motivates the individual to seek information about the product, provides the individual opportunity to evaluate the product, then helps the individual to purchase the product and eventually encourages the individual to tell someone else about the product. Marketers are responsible for managing this process and so we create and deliver messages to influence individuals to move to the next step. In many cases, we use the blanket term "customers" to refer to individuals at all stages, but these individuals are actually quite different. Clearly, someone who has never heard about the product needs different information (features and benefits) than the person who is evaluating a product (ratings and reviews) or a customer that has acquired the product (instructions). The most common names for individuals at these various stages are target, lead, prospect, customer, and advocate. A target is an individual who has not yet been made aware of the product. A lead is an individual who is a ware and receiving information about the product. A prospect is an individual who is educated about the product and evaluating the product. A customer is an individual who has purchased the product and is using it. An advocate is an individual who is spreading word-of-mouth.

A conversion model usually looks like a funnel because we need to reach many targets in order to win a few customers. An advertisement during the Superbowl, for example, may reach 120 million viewers, but fewer than 500,000 of them will actually act on the ad. If you pack 120 million grains of rice into a giant funnel and then apply pressure, hundreds, maybe thousands, of rice grains will trickle out the bottom and many grains will remain stuck in the funnel. Imagine the funnel has several holes in its side. As you apply pressure, grains of rice trickle out the bottom, but more grains fall out the sides. Similarly, many customers may see an ad, but most will abandon the process, some will get stuck somewhere in the process, and relatively few will turn into customers. Many individuals remain stuck at some step in the process because no company can satisfy the needs, preferences or expectations of everyone. Even in monopolistic sectors or life critical situations many individuals simply opt not to move forward because they are not properly incentivized to do so.

When an individual acts on a marketing message this is called a "response." We express the response rate as the number of responses to a message divided by the viewers or recipients of that message: R/V, where R is responders and V stands for viewers. When 120 million people view a Superbowl ad and 500,000 viewers respond, the response rate is 500,000/120 million or 4%. It is entirely normal and expected that the response rate to most media is lower than 5% and the actual response rate to television is even much lower.

When we build a conversion model, we are actually calculating the number of people at each stage in the decision-making process, which means we're calculating the size of our funnel. Funnels are usually very fat, but some are narrow. Coca Cola markets to billions of consumers in order to win millions of customers - it has a very fat funnel. On the other hand, Sun Microsystems markets to hundreds of IT professionals in order to convert dozens of them into clients. Sun has a narrow target segment and a relatively narrow funnel which it calls a"pipeline."

Before we can build a conversion model, we need some information:

- Budget. We need to identify a marketing budget.

- ROMI. Management has to establish some performance expectations.

- Price. A sales price has to be set

- Communication Costs. The expenses associated with promotions and advertising

- Process Costs. The expense of interacting with customers

Step 1. Design the Experience

The funnel matches the consumer decision-making process so list the actions you want customers to take toward purchasing your product. Although the decision-making process is usually 5 steps, the experience you design for your customer can include many incremental steps. You may have a 3-part information gathering phase or a 2-part evaluation process. I've seen conversion models with as many as 12 discrete stages. Remember, you can't ask customers to skip steps in the decision-making process and you cannot rearrange these steps, although sometimes we allow customers to consume a product prior to purchasing it, but you can combine steps. Events are a way of combining awareness, information, and evaluation into a single step. For this example, let's create a simple 3-step process: we want to influence targets to watch an online video, then we want leads to sign-up for a 30-day free trial, then we want prospects to buy an annual subscription.

- Targets see ad and go to website to watch video and become leads

- Leads sign-up for trial and turn into prospects

- Prospects buy annual subscriptions and turn into customers

Note that a three-step conversion process or customer experience has 4 stages:

- Targets. Consumers who we want as customers

- Leads. Targets who visit the website and watch the video

- Prospects. Leads who sign-up for a trial

- Customers. prospects who commit

Step 2. How many Customers?The next step is to calculate the number of customers needed - the number falling out the bottom of our funnel. Remember, customers refers to individuals who purchase the product. The number of customers is calculated by multiplying the marketing expense (or marketing budget) times the target return-on-marketing-investment (ROMI) and then dividing this sum by the product price: (ME x ROMI)/P, where ME is marketing expense, ROMI is the target return n marketing investment, and P is price. If your marketing budget is $25,000 and your price is $12, then you need 10,417 customers to achieve a target ROMI of 5x.

3. Calculate Prospects

Prospects, in this case, refers to individuals who are evaluating our product and are signed up for the 30-day free trial. If we want 10,417 customers, we obviously need more prospects. After all, the funnel gets bigger because not all prospects will turn into customers. To influence prospects to become customers, we have to do something. We have to invest in some interaction or communication that encourages the desired behavior. For our example, we decide to send each prospect a gift certificate via email and let's assume that similar prior offers generated a 40% response rate. This means that .4P=C, where P is prospects and C stands for customers. Thus, P=C/.4 = 26,043. In order to win 10,417 customers, we have to have 26,043 prospects and convert 40% of them. Emails cost $0.015 each to deliver so it costs us $390.64 to send those 26,043 prospects the gift certificate. Now we ca

n calculate the cost per acquisition (CPA) for this step, which is ME/R, where ME is marketing expense and R stands for responders. Therefore, the CPA for this step is $0.038, which means we will spend almost four cents to convert a prospect into a customer.

4. Calculate Leads

Leads are individuals who visit the website and watch an online video. If we want to capture 26,043 prospects, we need many more leads. After all, not everyone who visits the website will sign-up for the 30-day trial. To influence leads to become prospects, we have to do something. We have to invest in some interaction or communication that encourages the desired behavior. For this example, we will send each lead via email a newsletter. Based on our experience, we expect a 15% response rate. This means that .15L=P, where L is lead and P stands for prospects. Thus, L=P/.15 = 173,620. In order to win 26,043 prospects, we have to have 173,620 leads and we have to convert 15% of them. Emails cost $0.015 each so it costs us $2,604.30 to send the newsletter to those 173,620 leads. The CPA for this step is $0.10, which means we will pay ten cents to convert a lead into a prospect.

5. Calculate TargetsTargets are individuals who do not know about our product. If we want to capture 173,620 leads, we need many more targets. After all, the funnel gets bigger and not everyone who sees our ad will visit the website and watch our video. To convert targets into leads, we have to do something. Let's advertise on television. Based on testimonials from other advertisers during the same time slot, we expect a 1% response rate. This means that .01T=L, where T is target and L stands for lead. Thus, T=L/.01 = 17.4 million. The television station's media kit shows that the ad will actually reach 20 million viewers and will cost us $3 per thousand or $60,000. For mass media like radio, print advertising, and radio, we often pay to reach more customers than we actually need to reach in order to make our conversion model work and we'll adjust for this later. Only with direct media (email, mail or telemarketing) can we reach the exact number of target individuals that we want to reach.

6. Summarize Results

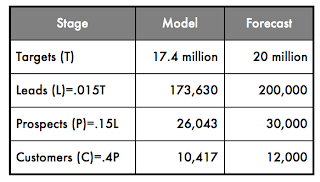

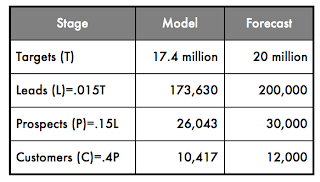

In order to make our conversion model work, we have to reach 17.4 million targets and convert 1% of them into leads, then we have to convert 15% of those 173,620 leads into 26,043 prospects, and finally we have to turn 40% of those prospects into 10,417 customers, who each spend $12 and generate $125,004 in revenue.

To do this, we have to spend $62,994.94 to communicate with customers and influence them to progress through the decision-making process. These expenses represent only our "communication costs." We have to also account for our "process costs," which in this case mean the expenses associated with interactions such as making the video and putting it on the website, the cost of giving away free trials, and the expenses associated with setting up new customer accounts. When we add these process costs to our communication costs, we calculate our total marketing expense. For this example, let's assume that the cost for creating the video is a fixed cost of $2,500, the cost of a trial is $0.25 per prospect or $6,510.75, and the cost of setting up a new customer account is $0.61 each to print and mail a welcome letter and membership card or $6,354.37. Our total process costs are $15,365.12. Our total marketing expense is $78,360.06.

The conversion model we developed says that if we spend $78,360.06, we will win 10,417 customers who generate $125,004 in revenue. This yields an ROMI of just 1.58, which is well below the goal set by management of 5x. Before we make adjustments to the model, lets see if the forecast gets us any closer to our goal.

7. Forecast

So far, we worked up through the funnel to find out what has to happen to make the model work. The conversion model represents what SHOULD happen. Now, let's figure out what will probably happen using real audience numbers for the media we selected to start this entire process.

Because we're using television, we'll reach a larger audience than we actually need to reach in order to make the model work, which is common for mass media. So we have to replace the target number in the model with the actual audience number and then recalculate the numbers for leads, prospects and customers, accordingly. Your funnel will get "fatter" because you're starting with a larger number of targets.

We spend $60,000 to reach 20 million targets and 1% convert to leads. Those leads watch a video that costs us $2,500 to make. Then we spend $3,000 ($0.015 each) to send 200,000 leads a newsletter in order to convert 15% of those leads into prospects. It costs us $7,500 ($0.25 each) to give prospects a free trial. Then we spend $450 ($0.015 each) to send 30,000 prospects a gift certificate via email in order to convert 40% of them into paying customers. We end up with 12,000 customers who spend $12 each and generate revenue of $144,000. We send new customers a welcome letter and membership card that costs $7,320 ($0.61 each). We forecast spending $80,770 and our ROMI will be 1.78.

Although our ROMI is positive in that the revenue generated by this campaign will exceed the total marketing expenses associated with it, the expenses exceed the budgeted amount and our ROMI is unacceptable.

8. Adjust

If your ROMI is not satisfactory, here are some things you can consider:

- increase price

- combine steps and shrink the process

- use more efficient media

- select less expensive media

- increase our budget

- improve conversion rates at one or more steps

- change our ROMI expectations

The Diffusion of Innovation bell curve illustrates how the use of a new product spreads through a population. Ideally, marketers want everyone in a market to immediately run out and buy our new products, but this is not realistic, because consumers differ in how willing they are to accept the risk of buying and using new products. It often takes months or years for most of the population to accept new products.

The Diffusion of Innovation bell curve illustrates how the use of a new product spreads through a population. Ideally, marketers want everyone in a market to immediately run out and buy our new products, but this is not realistic, because consumers differ in how willing they are to accept the risk of buying and using new products. It often takes months or years for most of the population to accept new products. stages to life cycle phases, lets use the data from the 100 villager example to calculate the stage sales and sales growth for each phase of diffusion.

stages to life cycle phases, lets use the data from the 100 villager example to calculate the stage sales and sales growth for each phase of diffusion. n calculate the cost per acquisition (CPA) for this step, which is ME/R, where ME is marketing expense and R stands for responders. Therefore, the CPA for this step is $0.038, which means we will spend almost four cents to convert a prospect into a customer.

n calculate the cost per acquisition (CPA) for this step, which is ME/R, where ME is marketing expense and R stands for responders. Therefore, the CPA for this step is $0.038, which means we will spend almost four cents to convert a prospect into a customer.